Dec 01 Coming Face-to-Face with Abstraction at Hartwood Acres

This guest blog post was written by University of Pittsburgh History of Art and Architecture student, Layne Shaffer.

When you walk through the lush landscape of Hartwood Acres, you would hardly expect to come face to face with abstract steel – welded and bolted to the ground, sitting on the concrete slabs that many of these sculptures call home.

I can imagine that sometimes an exhausted runner or a dog walker, weary from sleep, sees these sculptures and thinks “What could that possibly be?”.

And to that I answer, exactly.

I had the privilege of being invited onto the Hartwood Acres Sculpture Garden project by Professor Alex Taylor as a museum studies intern at the University of Pittsburgh along with two other students. This project was in conjunction with Shift Works (formerly the Office for Public Art) Education and Outreach Program Manager Rachel Klipa as well as the Allegheny County Parks Foundation. As an Allegheny County park, Hartwood Acres began its sculpture garden in 1979 largely due to Carol R. Brown, who was the director of Allegheny County’s Bureau of Cultural Programs to which the garden owes its name. [i] This project came at a time when the public art initiative in Pittsburgh was looking toward contemporary sculpture.[ii] Our goal was to research and develop interpretive material for the fourteen sculptures at the site. My first time seeing these sculptures was in early January 2023. We made the drive up to the site on a cold and dreary day. We stood in front of each sculpture – many in bright hues against their gray backdrop – and tried to make sense of them.

We stood in front of North Light by David Von Schlegell, its bright white appearance unmistakable as you drive up the curving road to arrive at the Hartwood Acres mansion.

Once I had started researching David von Schlegell, the first thing I learned about his sculptures was that he didn’t want you to liken them to anything. He preferred interpretations of his work to be left up to the imagination, rather than him or anyone else telling you what it is.

Before this project, I had not had much exposure to modern or contemporary art, and far less with public sculpture. At first, I did not have much in the realm of art historical critique to bring to the table. But, personal opinions about an artwork are not faux pas. At first, I was not sure how I felt about nearly all of the sculptures at Hartwood Acres. But, I had many, many questions, and was very eager to learn more.

I have spent a total of nine months working with these sculptures, researching the artists and applying that knowledge in a way that can help the public appreciate them like I now do. I had the privilege of being able to extend this project into summer 2023, working as an HAA Fine Foundation Fellow with the Office for Public Art. To cumulate all of this research into writing that would be accessible to the public forced me to step back into the shoes of the person that stood in front of these sculptures in January. I had to ask the questions: what do people need to know? But, more importantly, what do people want to know? During the walking tour we conducted of these sculptures in August 2023, this was vitally important. What would keep the tour goers on their toes during a two hour tour?

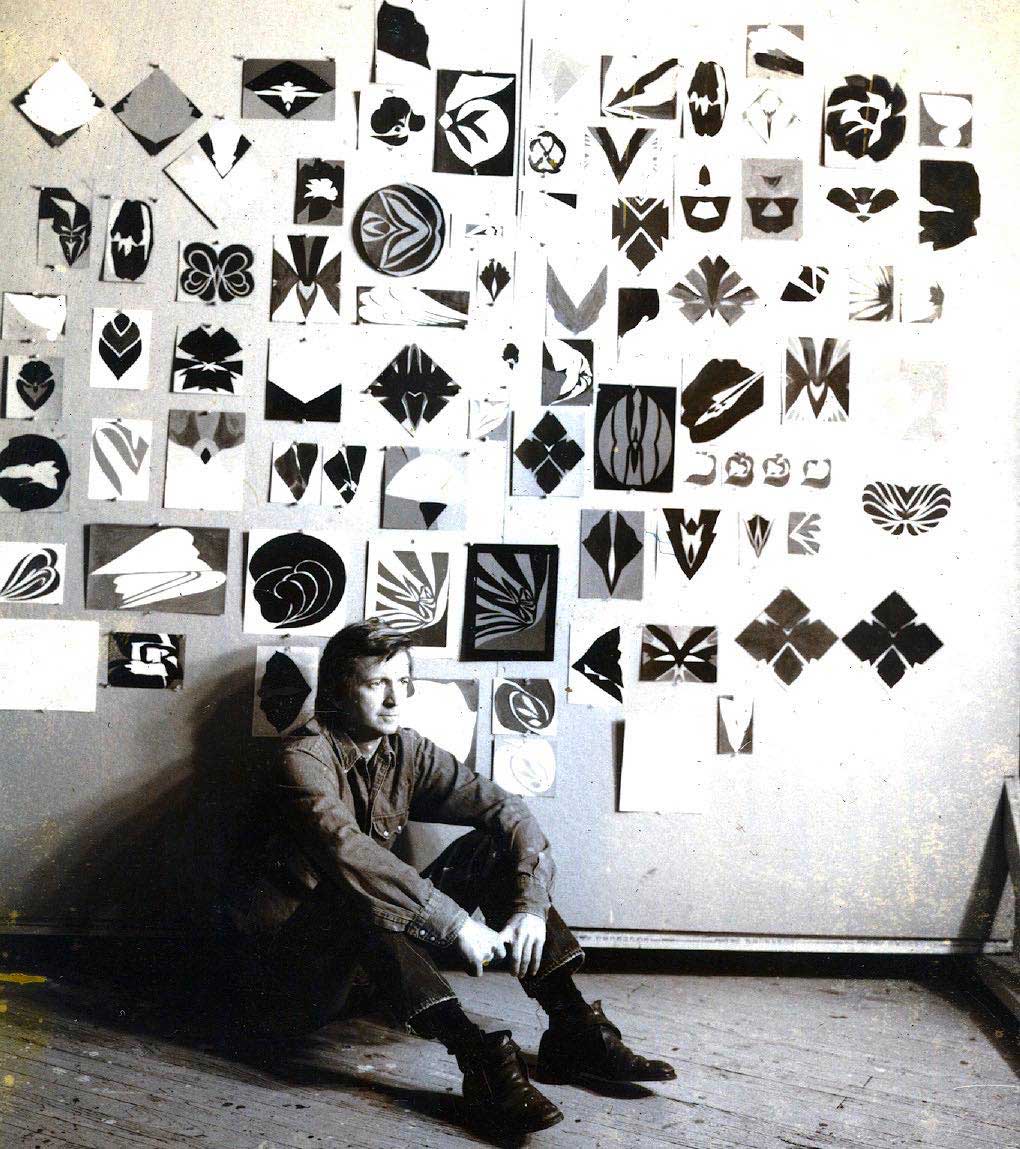

Jack Youngerman was a painter. At the start of my research, I was inundated with information not about his sculptures, but his accomplished career as a painter. I thought that, in an effort to remain grounded in my research, I could focus only on his sculpture rather than his paintings. I quickly found that this was impossible. In order to understand his sculpture, I had to understand his paintings. And, truthfully, I had to understand his paintings before I found myself actually liking them.

Jack Youngerman’s Totem:Lamina:Limbus, 1979 are three distinct sculptures which were first realized in the two dimensional. Totem Blue was a woven tapestry made by Youngerman. The sculpture Limbus, in red, can be traced to ink drawings found in images of Youngerman’s studio. Lamina is perhaps reminiscent of the broad part of a leaf, called the lamina. Youngerman stated about the forms found in his art, “They are not abstracts or shapes of specific things, but they have obvious references. It is impossible to have a form which doesn’t make the viewer think of something he’s seen before.”[iii]

Youngerman quickly became my favorite artist. It is very easy to take an artist too seriously, especially if their art explores abstract forms like Youngerman. But, if he was able to have fun, why shouldn’t those who are learning about him also have fun? His artistic career began in Paris, where he attended the Ecole des Beaux Arts under the G.I. Bill after serving in the US Navy during WWII. When asked why he chose the Navy, he said it was because he “liked their uniforms better.”[iv] A man of taste.

These were the bits of information I thought it was important to share with the public on our walking tour. It juxtaposes the towering pieces of steel that stand in front of you, which would perhaps feel impersonal or inaccessible if you did not feel a connection to the artist or the space to make your own associations, like Youngerman allows.

The thing about these sculptures, and these artists, is that they do not beg you to like them. In fact, sometimes, they want you to dislike them. Like Ron Bennett, sculptor of Cloudt, 1982 stated, “If it evokes a response from the viewer, even negative, then I’m happy.”[v]

Sometimes, I think, seeing a work of art you dislike and claiming “I don’t like that! How is that art?” is in an effort to separate yourself from it. I have certainly been guilty of this in the past. If you see a weathered steel cube in the shape of a cloud on the grass at Hartwood Acres and think the same thing, Ron Bennett sees that and raises you one higher.

These sculptures, which surround the Hartwood Acres Mansion, are open to the public from sunrise to sunset. Our research will be implemented in various ways to the public, one of which being Park Ranger tours conducted through Allegheny County for those interested in learning more about the sculptures. You can also enjoy a self-guided tour by using the map and information found here.

References:

[i] Klipa, Rachel and Rao Heffley, Divya. “The Sculpture Garden at Hartwood Acres”. Office for Public Art, October 2019, 3.

[ii] Ibid, 1.

[iii] “Dartmouth exhibits work of artist Jack Youngerman,” Bennington Banner, October 23, 1975, 11.

[iv] John Gruen, “Jack Youngerman,” in The Artist Observed (A Capella Books, 1991), 206-217.d

[v] Virginia Miller, “People Form Opinions on Harwood Sculpture,” North Hills News Record, April 6, 1982, 10.